Kodak: A journey from creating memories to bankruptcy

By Aniket Gupta | 06 Mar 2024

.jpg)

“Your pride comes before a fall.”

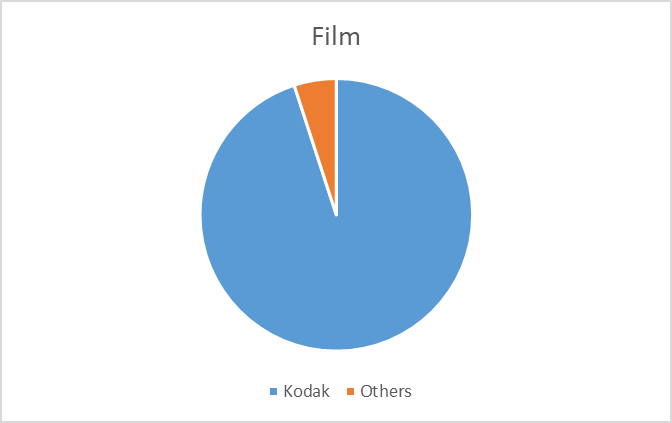

Have you ever seen a Kodak camera, or heard the name of this company, the Eastman Kodak Company? If not, ask someone in your family who is over half a century old. The name Kodak doesn’t suggest much today, but there was a time not so long ago when Kodak had a near monopoly in the photography business. Both cameras and film.

.jpg)

Back in the 1970s, Kodak used to rule the world of photography. It was the biggest photography company in the world. So big that there is a 90% chance that if you look at a picture clicked 50 years ago, it was probably clicked by a Kodak camera, captured on Kodak film and then printed on Kodak paper. And why I say “near monopoly” is because Kodak had while Kodak had a few competitors, such as Fuji, Nikon and Canon, these other companies’ were market share was nowhere near Kodak’s.

Look at the chart below. According to data published by Bloomberg, Kodak controlled 95% of the film market and 85% of the camera market in 1976.

Film and camera were the two of Kodak’s main businesses.

Birth of Kodak

Kodak was founded in 1888 in Rochester in New York state in America.

.jpg)

The full name of Kodak is actually Eastman Kodak Company, and it was started by two men, George Eastman and Henry Strong. Before they started Eastman Kodak in 1888, they had started another company named Eastman Dry Plate Company, which used to sell dry plates for cameras. Then, in 1884, George Eastman started to develop a camera of his own by replacing glass plates with new roll film.

.jpg)

We can figure out how the word Eastman got incorporated into the company name, but where did Kodak come from?

The answer is: nowhere.

George Eastman just wanted a unique name that sounded simple and would stay in people’s minds. So he came up with ‘Kodak’. Originally, Kodak was the name given to his camera, but later he decided to name his entire business Kodak.

.jpg)

What about Henry Strong? Well, he is credited as the founder of the company, but he was more of an investor than hands-on businessman. So it was mostly Eastman’s baby.

.jpg)

Now remember it’s the 19th century we are talking about, when people had to go through hell to just click a photograph. The process was too lengthy. The cameras used were too heavy, and the photographs needed to be developed immediately, so all the supplies required to do that had to be carried along. Then, Eastman came into the picture, and he brought all the innovations with him, like Santa Claus bringing a bagful of presents at Christmas-time.

Eastman’s innovation made photography much easier and more accessible to the general public. That was reflected in the company’s earliest slogan, which was, ‘You press the button, we do the rest’.

.jpg)

When Kodak came into existence with its ‘one-click camera’, the process of clicking pictures became easier, but it didn’t become cheaper. The process was still expensive. People would buy the camera; click a few pictures and send them to a Kodak studio, which would develop the pictures for you, charge a small fee, and send them to you.

This is a classic case of the ‘razor and blade’ business model, in which companies sell high-margin products at a low price to increase the volume of sales. The increased sales volume then complements the sale of another low-margin product.

.jpg)

In the case of Kodak, the high-margin product was the camera with a built-in film roll that could store 100 pictures, and the low-margin product was the processing fee Kodak charged to develop the photos.

Kodak made the camera cheaper but then also added the processing cost to it, thereby increasing the overall cost. So by doing this, even though consumers thought they were buying cheap cameras from Kodak, they were also being forced to pay a small processing fee.

.jpg)

This process gave birth to the Brownie. No, not the delicious chocolate cake, but a camera with that name. And wonder of wonders! That Brownie cost only $1. This product helped Kodak boost its sales in the later years of the 19th century.

Although the whole process of developing a photograph was expensive, these peculiar innovations were far superior to those of its competitors. Kodak’s popularity zoomed.

Early legal troubles

One of the earliest obstacles Kodak faced was during the making of its first camera. When George Eastman was still creating his first camera, he was forced to pay a sum of money to David Houston. This payment was demanded for the license of some pre-existing patents.

Later, Kodak had to tackle a major lawsuit for patent infringement from Ansco, which was a rival camera film producer to Kodak. In 1887, another contemporary inventor, Hannibal Goodwin, filed a patent for nitrocellulose film. This patent was filed before Kodak had filed its own patent. The patent office had first rejected Goodwin’s initial filing, but later in 1898, Goodwin was able to convince the patent examiners and got his patent.

In 1900, Ansco, a rival photography company, purchased the patent from Goodwin, and later in 1902, they sued Kodak for patent infringement. This case was taken to court, and finally, after more than a decade, in 1914, the lawsuit was finally settled for $5 million, which Kodak had to pay.

The 20th century

In the late 1920s, during the Great Depression, Kodak faced some major challenges, including a 17% reduction in its workforce between 1929 and 1933. George Eastman’s health decline and other problems led to his tragic suicide on 14th March, 1932.

Despite the economic downturn, Kodak headquarters in Rochester fared better due to resilient banks.

In response to the unemployment crisis, Kodak joined the Rochester Plan from 1931 to 1936. Rochester Plan was a privately funded initiative to aid jobless individuals and stimulate consumer spending. The plan was supposed to request all the big private companies and banks of Rochester to fund, and Marion Folsom, an American government official and a former Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, spearheaded the program, leading to substantial improvements within Kodak. However, its impact on the general population of Rochester was limited, as few companies participated.

Amid these challenges, Kodak continued to survive and diversified its business by producing industrial high-speed cameras, vitamin concentrates, and plastics. Additionally, a partnership with Edwin Land, an American scientist and inventor, in 1934 paved the way for Kodak’s involvement in supplying polarized lenses. Polarized lenses are mainly used to reduce the reflection of other objects or glare of the sunlight, and enable the camera to take better pictures. Edwin Land later founded the Polaroid Corporation, creating the first instant camera using Kodak-supplied emulsions.

.jpg)

Leadership changes within Kodak occurred with Frank Lovejoy taking over as president in 1934, succeeding William Stuber, and Thomas Hargrave assuming the presidency in 1941.

Kodak continued to innovate during the 1930s and created Kodachrome in 1935. Kodachrome was a unique three-color film that could be used to develop color images.

.jpg)

Fun fact: Celebrated American singer and songwriter Paul Simon created a chartbuster song titled Kodachrome in 1973.

Kodak and politics

During the Second World War, a group of Kodak scientists joined the Manhattan Project, contributing to the enrichment of uranium-235 at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

During the Cold War, Kodak participated in covert initiatives launched by the US government. From 1955, it partnered with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the Bridgehead Program, crafting cameras and film for the U-2 spy aircraft. Kodak collaborated with the National Reconnaissance Office on surveillance satellite cameras. In the 1960s and 1970s, Kodak engineers contributed to the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, designing optical sensors for a crewed reconnaissance satellite. A subsequent study for NASA explored the astronomical applications of MOL-derived equipment.

Business strategies implemented by Kodak

Other than government projects, Kodak applied some unique strategies to expand its own business. One of these was to add the cost of processing photographs to its camera prices. So, people who were using the camera and film made by Kodak were forced to get their photos processed by Kodak, and Kodak alone.

However, in 1954, a court pronounced that Kodak’s method of creating a monopoly with cameras, films, and processing was unfair to other competitors and therefore illegal. After that, Kodak had to bring down the price of its films, and finally, in 2009, the company stopped making films.

Another secret to Kodak’s success was its genius marketing campaigns. Kodak had started a marketing campaign known as ‘The Kodak moment’.

In the 1960s, the phrase ‘Kodak moment’ started appearing in the company’s advertisements. ‘Kodak moment’ played with the power of nostalgia. If you have a moment you want to remember for the rest of your life, click a picture of it, and it becomes a Kodak moment. This campaign was a game changer, as more and more people started buying Kodak products. Kodak ruled the photography market in the 1970s and 1980s.

But then the 1990s came, and the competition hotted up.

Emergence of competitors

In the 1980s, Japanese competitor Fujifilm entered the U.S. market with affordable film and supplies, securing the role of official film for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. This victory granted Fujifilm a lasting position in the market. With a U.S. film plant and strategic marketing, Fuji’s market share rose from 10% in the early 1990s to 17% in 1997, challenging Kodak.

.jpg)

Facing pressure, Kodak implemented cost-cutting measures, leading to increased revenues and profits in the 1990s.

In May 1995, Kodak submitted a petition to the U.S. commerce department under section 301 of the Commerce Act, alleging that Fuji’s unfair practices were responsible for Kodak’s underperformance in the Japanese markets. The US government forwarded the complaint to the World Trade Organization (WTO). On 30th January 1998, the WTO declared a comprehensive rejection of Kodak’s complaints .

A price war with Fujifilm impacted Kodak’s profits, with revenues dropping from $15.97 billion in 1996 to $14.36 billion in 1997. Market share in the America declined from 80.15% to 74.7%. Both Fuji and Kodak anticipated the rise of digital photography, but Fuji’s successful diversification efforts outpaced Kodak’s.

Rise of digital photography

Today, if we look back at film photography and Kodak, it would be easy to state that the evolution from film photography to digital photography was the reason behind Kodak’s downfall. The statement would be true, but not entirely so. In fact, in 2005, the market leader for digital cameras in the U.S. was Kodak. But 2005 was also the year when things started to look difficult for the company.

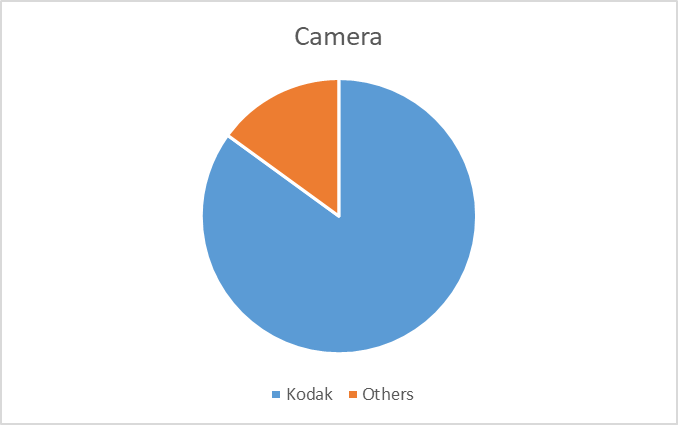

The company had started to report weak sales numbers, and the downfall had started. Refer to the chart below for the sales figures of Kodak from 1992 to its bankruptcy in 2012.

As you can see from the chart, Kodak reported strong sales figures in the 1990s. Its 1996 sales ($15.9 billion) were among the highest the company had ever recorded. Unfortunately for Kodak, less than a decade after that, sales started to drop. And then they plummeted.

Finally, in 2012, Kodak had to file for bankruptcy. As mentioned before, the digital camera was one of the reasons behind this downfall. But that was not the only reason. Kodak knew about the digital camera market and also made some efforts to sell digital cameras, but not nearly as much as it should have.

You would be astonished to know that the first digital camera was created in 1975 by a Kodak employee named Steve Sasson. In 1978, Kodak received a patent for this product. The trend toward digital cameras was on the rise in the 1990s, and Kodak too started selling these cameras.

.jpg)

But then a very important question arises. How come a company that created a product and even sold it, had to file bankruptcy due to the same product they had created?

“I hope it never gets big, because then our film sales would suffer." – Steve Sasson

This statement made by the creator of digital cameras perfectly encapsulates the reason for Kodak’s downfall.

The answer is: film sales. Kodak had made camera film the core product of the company. Although it used to sell cameras as well, cameras were not a very profitable part of its business. Kodak had been creating and selling camera film for a hundred years when the first digital camera was born. It was very clear that Kodak wanted camera film as their most important product, even after digital cameras came into existence.

.jpg)

It was an expert in making camera film. And it wanted consumers to believe that films cameras were still far superior to digital cameras.

The fall of Kodak

Kodak faced a financial downturn, leading to a $300 million loan from KKR in 2009. To repay debts, Kodak sold its divisions, including the profitable Kodak Health Group, raising $2.35 billion.

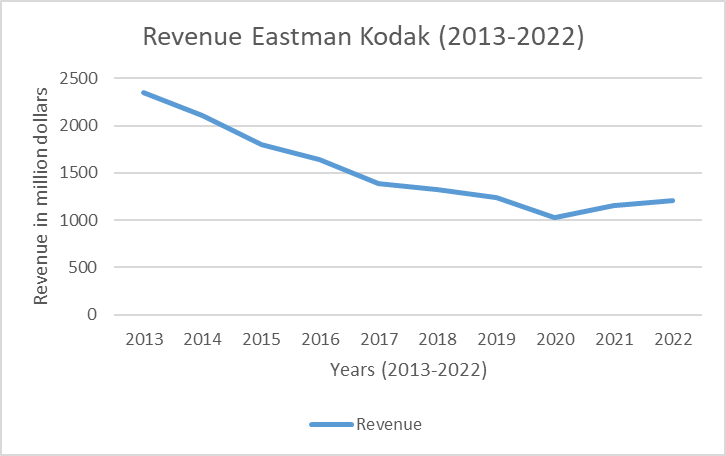

Refer to the chart below to see the fall in revenue for Kodak post-bankruptcy.

In order to tackle falling revenues, Kodak turned to patent litigation, earning $838 million in 2010, including a settlement with LG Corporation. However, by 2011, with dwindling cash reserves and fears of bankruptcy, Kodak had explored selling or licensing its extensive patent portfolio. In January 2012, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, obtaining a $950 million credit facility from Citigroup. During bankruptcy, Kodak sold patents for around $525 million to companies such as Apple and Google.

The decline and bankruptcy of Kodak had a significant impact on Rochester, causing job losses and even contributing to a high poverty rate.

Kodak did emerge from its bankruptcy in 2013 and started focusing on imaging for business, with segments in digital printing and enterprise and graphics, entertainment, and commercial films.

What do we learn from Kodak?

Let us look at an average person in 2024. Nearly everyone possesses a mobile phone with a camera. These cameras surpass the quality of those offered by Kodak and its competitors in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, as highlighted in this article, the key is innovation. Kodak had stopped innovating leading to its near-demise in an industry in which they once had the monopoly.