The Bata vision

By Kiron Kasbekar | 22 Nov 2023

I find it strange that some big companies keep themselves shut off from public view. Not their products, of course, for the products are on sale worldwide. But their financial data. They do not feel obliged to reveal information because their shareholding is tightly controlled by a family or a close group of people.

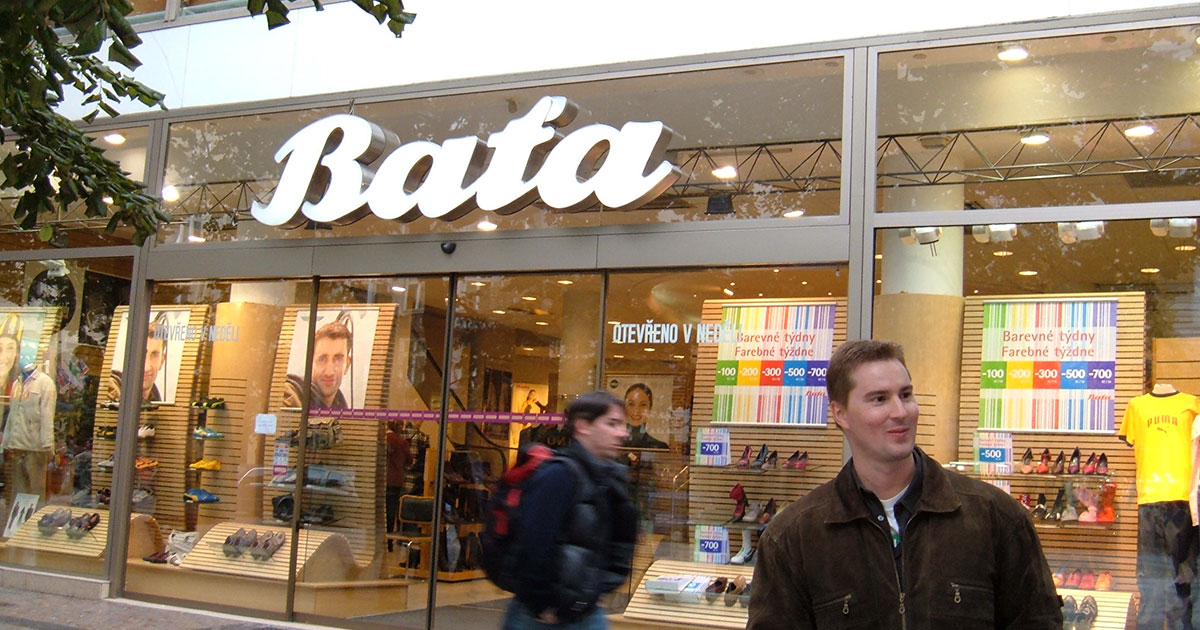

Bata is one such group.

Look at its rivals Nike and Adidas, whose finances are not a closed secret. Nike had revenues of $51.22 billion in 2023. Adidas was smaller, and, even after acquiring Reebok in 2005 for $3.8 billion, it had revenues of, $23.6 billion in 2022. Not small by any measure, but smaller than Nike.

But I cannot give you a precise figure for Bata; all I can say is that it too is very big. If it were an Indian company, it would figure in the list of the private sector’s top 10 or 15 non-financial business groups in the country.

Bata is not very open about its business because it is a closely held, family-owned company. But we do know a few things about Bata.

This is big!

It is reported that Bata employs more than 32,000 people, runs more than 5,300 shops, and serves over 1 million customers daily in over 70 countries. And it runs 21 production facilities.

In comparison, Adidas had 2,184 stores worldwide in 2021, and Nike had 2,592 as of 11 November 2023, according to its website. Bata had around 4,700 retail outlets. That should not be directly translated into financials; for Bata products are mostly much lower priced compared to Adidas and Nike products.

Adidas reported 57,334 employees, according to its first-half statement for 2023, and Nike reported 83,700 employees worldwide, including retail and part-time employees, in 2023.

Cobblers in the past

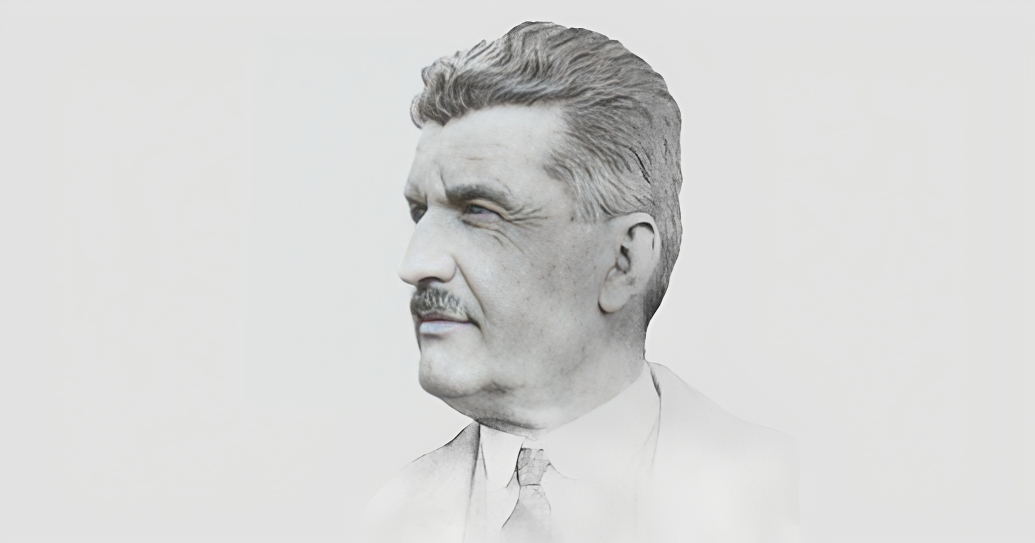

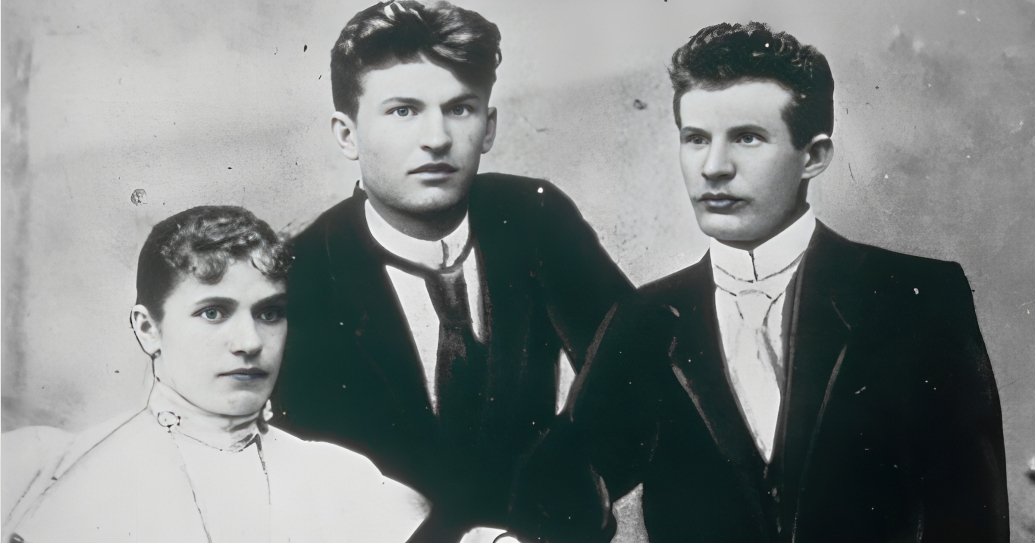

Bata traces its roots back to 1580 in the cobbling trade in Zlin, a small village in what is the Czech Republic today. The family trade grew slowly, and then, in 1894, the family graduated from being cobblers to becoming industrialists. That was when Tomas G. Bata, Sr., his brother Antonin and his sister Anna invested 800 florins, or about $350, left to them by their mother, in a somewhat bigger shoemaking business.

The siblings rented a couple of rooms, bought two sewing machines, procured leather and other stuff, and began stitching coarse footwear with woollen uppers. They met with success, and a year later they employed ten people in their small factory, and around forty others who worked out of their own homes.

Before long Antonin was drafted into the army, and Anna left the business to get married. That left 19-year-old Tomas in complete control of the business.

Tomas was not deterred. In 1900 he shifted the business to a new building near the Zlin railway station, and then installed steam-driven machines to improve productivity. The firm produced light, linen footwear that a large section of people liked because it was cheaper than the usual leather shoes.

Verge of bankruptcy

But making cheaper shoes was not the easiest way to make a fortune. Bata came to the brink of bankruptcy, and decided he had to find more efficient methods of producing and distributing shoes.

What would the average shoe-maker do? I don’t know, but, I imagine, not what Bata did. In 1904, he traveled to America along with three employees to learn how mass production worked.

Bata worked for six months as a laborer there in an assembly line in a New England shoe factory. Then he visited English and German factories on his way back home.

Then in Zlin he began to introduce the latest production techniques he had learned on his travels. But he did one more thing. He found ways in which to retain the artisan’s role workers played in the business, which modern manufacturing had caused to diminish and get dehumanized.

After that, the business grew steadily. By 1912 Bata had 600 full-time workers working in his factory, and some more hundred working from their homes in nearby villages.

Houses for workers

Bata was not satisfied with the increased sales and growing profits. Ever the idealist, he decided to do something about the housing shortage in Zlin that troubled workers in his factory.

So he built houses and rented them out at cost to his workers. Workers also got low-priced meals in the factory cafeterias. And they got free medical care. A new hospital was built to treat workers. Company stores were opened to provide low-priced goods for employees.

Soon Bata began to select managerial talent from among the workers and made them go through a training program. Which was an extraordinary thing for its time.

Then the First World War started. While it caused much economic disruption, the demand for boots shot up. Soldiers needed sturdy boots, and Bata was among the firms that received big contracts for boots for the Austro-Hungarian army. Remember, Zlin, a town in Czechoslovakia, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time.

Not content with getting the army order, Bata used the waste from this trade to make uppers for wooden shoes he sold to poorer customers.

Not one to rest on his oars, Bata ploughed back his profits in new machinery and new shops, and that placed his business in a very good position to benefit from the 1920s economic boom. But before that happened, Bata had to deal with a crisis.

Dealing with a crisis

In 1918, after the First World War ended, the post-war slump dampened business prospects, and businessmen in the region were completely disheartened. The currency had crashed, there was severe unemployment, which resulted in demand plummeting – and businessmen were pessimistic and lost. But not Bata.

Bata prepared a plan. A plan that meant drastic restructuring, but a plan that was feasible. He slashed costs to the bone and motivated his workers to work at the highest possible efficiency – so that they could cut Bata shoe prices by half.

Union leaders demurred; but the workers ignored their protests and accepted a 40 per cent wage cut. Bata did his bit by supplying food, clothing, and other things at half their normal prices.

Simultaneously with that, Bata created productivity-linked incentive systems for both management and workers.

Having improved the firm’s operations Bata launched an advertising campaign. Consumers responded favorably, and Bata stores, which had seen few footfalls for some time, found a large number of customers keen to buy inexpensive shoes.

Expansion

Then Bata increased production. The company, which had been able to maintain full employment, now began to hire more workers. The price cuts marked a turning point in the company’s history, and sales shot up.

Bata’s innovation resulted in the company adopting the assembly line approach, which resulted in productivity improving 15-fold in 5 years. That resulted in lower costs, and helped Bata slash the retail price of its shoes by 82 percent.

The company rewarded its employees too, doubling their wages in 1932 after having enforced severe wage cuts a decade earlier.

Bata became the world’s biggest shoemaker.

Then Bata invested in other, mostly related businesses, such as socks, leather chemicals, shoemaking machinery, wooden packing crates, tires and other rubber goods. What’s more, Bata launched its own studio to create advertising films, and that evolved into an enterprise in its own right, producing animated films.

And then Bata took a leap into aircraft manufacture, creating the Zlin Air Company for the purpose.

In 1931 Bata converted itself into a joint stock company, and established subsidiaries and shoe factories in several European countries. The idea was to avoid import tariffs imposed in most countries during the worldwide economic depression.

However, in mid-1932, before he could see the results of all the changes he had launched, Tomas Bata was killed when the aircraft he had boarded took off in a thick fog and hit a chimney of one of his buildings.

Bata was just 56 years old when he died. Had he lived longer, who knows what more innovations he might have begun!

This was the story of Tomas Bata, the founder of the Bata empire. Today the company is run by the third generation of the Bata family.