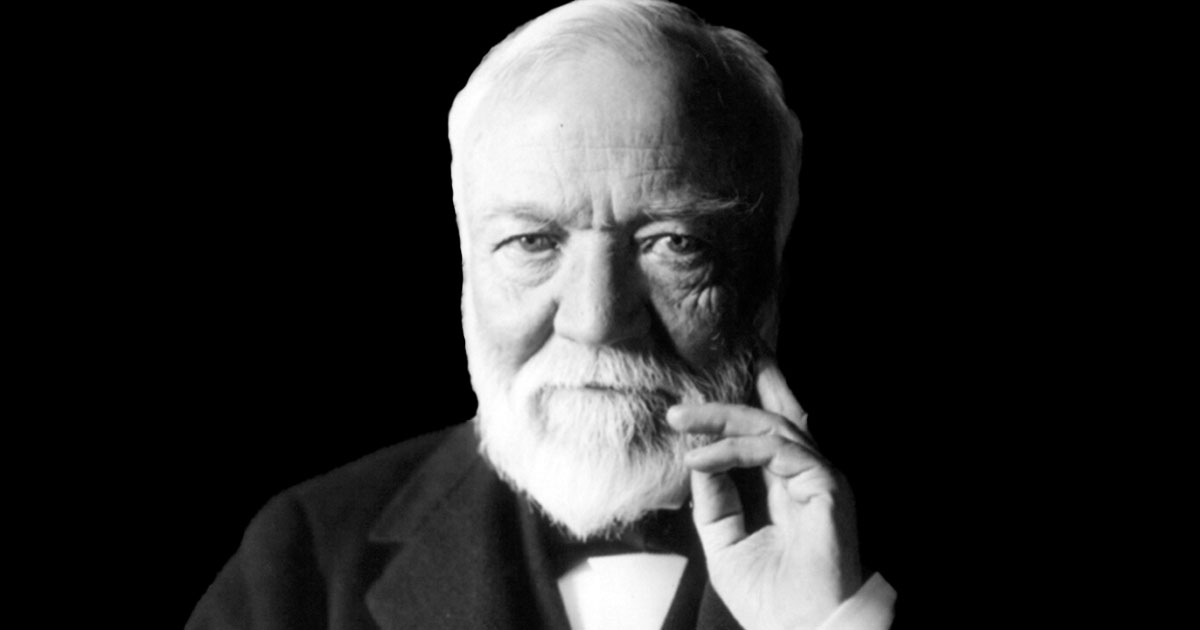

Andrew Carnegie: The man who shaped America’s steel industry - Part 2

By Aniket Gupta | 27 Oct 2023

The parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son - Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie created one of the biggest steel businesses of the 19th century. He introduced many innovations in his steel mill in Pittsburgh and implemented new ways to cut costs and maximize efficiency.

In the Part 1, we explored how Andrew Carnegie started his climb to the top. But generally, in the business world, staying on top is more difficult than getting there. Andrew had made some rivals in his journey to the top. One such businessman who crossed paths with Andrew Carnegie was John D. Rockefeller, a well-known oil magnate.

Clash of the titans in the 19th century

In the second half of the 19th century, Carnegie’s biggest clients, the railroads, started to face some major problems.. The mass production of rails fueled a rapid expansion of the railroads, and created intense competition between railroad companies.

Around that time, the American economy slowed down, and the stock market crashed. This caused more problems for the railroad companies. Carnegie and his steel mill were also affected, for he was not able to get sufficient orders from his biggest clients.

John D. Rockefeller, a rich oil magnate, saw a great opportunity amid this crisis and decided to capitalize on it. Knowing how desperate the railroads were for more cargo, Rockefeller negotiated a huge discount with them to ship very large quantities of his oil on the railroads at a much lower price.

The deal was not sustainable, and many railroad companies went bankrupt. Thomas Scott, Carnegie’s old mentor, was one of those businessmen who was bankrupted.

Carnegie then resolved to beat John D. Rockefeller in wealth and started looking for other sectors to which he could supply his steel.

He decided to enter the market for building skyscrapers in big cities such as New York and Chicago. To grow big in this business, he sought help from outside.

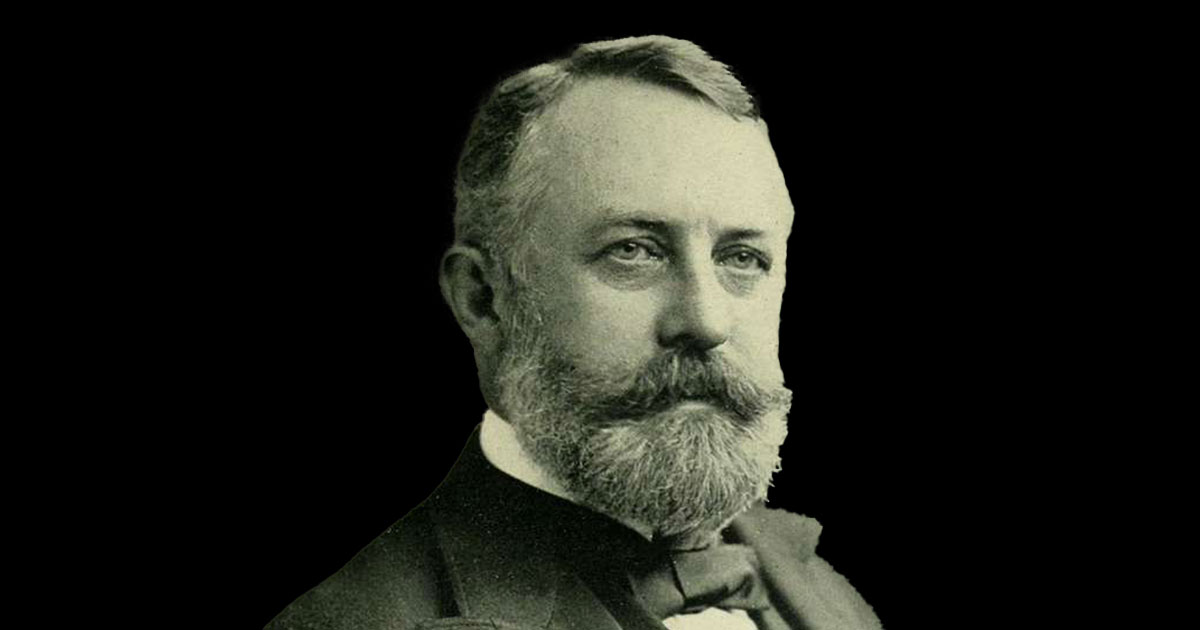

He found a man who was perfect to help him grow the business. This man was Henry Clay Frick. Unfortunately, this partnership will go down as one of the most infamous business partnerships in American history.

A partnership forged in hell

Frick was a stubborn man with a no-nonsense attitude. Before he met Carnegie he had gained notoriety for his cut-throat attitude. And Carnegie thought he was the perfect candidate to help him expand his business, for Frick was known for getting what he wanted by any means necessary.

Together, Carnegie and Frick generated a pile of money – but most of it came at the expense of other people’s livelihoods.

In their joint quest to completely dominate the steel industry, Frick renegotiated contracts with suppliers for Carnegie’s company using the tactics of fear and intimidation. Carnegie had started portraying Frick as the face of the company, which helped the steel baron deflect any criticism that might be directed at him.

Frick started cutting down workers' wages despite making vast profits. Then, as he started a hectic expansion of the business, he came up against Duquesne Steel Works. Duquesne had started producing steel more efficiently than Carnegie’s steel mill by using more advanced machinery.

So what did Carnegie and Frick do? They used dirty tactics, such as spreading false rumors about Duquesne steel being defective, and that affected its credibility in the market. Soon, Carnegie Steel was able to buy out Duquesne Steel at a bargain price.

After this, production started to increase even more, which allowed Carnegie and Frick to buy out other competitors in the area and open more steel mills. Carnegie’s personal wealth soared.

Disaster

Frick had established an exclusive club in the hills of Pittsburgh for the wealthiest men in America. It was called The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

The club wanted its own private lake to fish on, so it took control of the South Fork dam. This dam was just 14 miles from a small town named Johnstown, which housed industrial workers and their families. The dam was also one of the largest dams in America and held around 20 million tons of water.

There were many concerns over the changes the club had made to the dam, which, it was said, weakened the structural integrity of the dam. The club turned down all requests to strengthen the dam. Then disaster struck.

In 1889, the dam breach during a rainstorm claimed 2,209 lives, including around 400 children, with bodies discovered years later, some even hundreds of miles away.

The Johnstown flood marked the worst man-made disaster in American history at that time. Members of the club, including Frick and Carnegie, used their money and influence to prevent any backlash from the disaster falling on them.

Battle of Homestead

Another infamous incident that directly involved Henry Frick was the conflict at Homestead.

It seemed evidently clear that Carnegie was using Frick to do his dirty work while he kept his own image clean. The Battle of Homestead was a big conflict in which Carnegie kept his distance – literally as well figuratively.

Carnegie had bought another steel mill known as Homestead. The workers here had formed unions in order to negotiate better wages and working conditions. Carnegie left Henry Frick in charge of the negotiations and went off to Scotland for a long vacation.

Frick had clear instructions from Carnegie not to entertain any wage hike demands from the workers and to dissolve any trade unions that were formed. Carnegie had also increased output so as to build a buffer stock of steel in case negotiations failed and the workers decided to strike work.

Unfortunately, no one could have predicted how the negotiations would actually go.

Frick had repeatedly turned down all demands of the workers. What was worse, he informed the workers that he was going to cut wages by 22 per cent. This agitated the workers, and they stood firm with no intention of backing down.

On 25 June, as the workers’ union refused to back down, Frick announced he would no longer negotiate with the union and would only deal with workers individually. On 29 June, on orders from Carnegie, Frick closed down the steel mill and locked the workers out.

This was done with the expectation that the workers would yield and soon rejoin work. But the workers initiated a strike, and thousands of them took control of the mill. They barricaded themselves in front of the Homestead steel works, effectively blocking Frick from bringing in replacement workers to fill their positions.

Frick hired the Pinkerton agency to provide armed escort for black legs brought in to replace the striking workers. On 6 July 1892, a battle erupted between the Pinkerton men and the striking workers. The battle raged for 12 hours, and it is estimated that nine Homestead workers were killed, seven Pinkerton army men were killed, and countless people on both sides were injured.

After analyzing the severity of the situation, the Pennsylvania governor sent in the state militia to restore order. The workers had to finally surrender and call off their strike. Frick reopened the steel mill and brought in cheaper replacement workers. That left many of the original workers without jobs.

Since this brutal confrontation between workers and Frick, the steel industry did not see any more worker unions for the next 45 years.

Frick versus Carnegie

There was a public backlash against Carnegie after the strike ended. In his autobiography, he stated, ‘nothing in all my life before or since wounded me so deeply’ and ‘had I been there, the tragedy would not have occurred’.

Some historians argue that Carnegie’s presence could have prevented the escalation of the strike. Carnegie built a library in Homestead in honor of the men who lost their lives during the conflict.

Frick, on the other hand, felt that Carnegie was unfair in laying all the blame on him. The two had a bitter falling out in the aftermath of the strike. Frick eventually filed a lawsuit seeking the market value of his shares in the company.

This legal action became one of the most prominent private lawsuits in American corporate history. The courtroom drama drew widespread attention from national newspapers, making it a compelling narrative — a clash between two industrial titans who were once allies, now engaged in a sordid spectacle of deceit, betrayal and vengeance.

The lawsuit brought out the financial details of the company, which had been largely concealed until then. It revealed that Carnegie Steel was on track to generate approximately $40 million in profits by 1900, equivalent to about $1.4 billion in today's currency.

These numbers had been deliberately kept under wraps by Carnegie in order to have a better bargaining position vis-à-vis workers and suppliers. Ever the shrewd businessman, he forestalled further disclosure of the company’s information in court by reaching a settlement with Frick.

Under this agreement, Carnegie bought out Frick for $31.6 million, in exchange of which Frick relinquished his managerial positions within the company and withdrew his lawsuit.

A deal brokered between the titans

At the turn of the 20th century, Carnegie found himself touching his 70s. With growing age, he found it difficult to manage his steel empire and decided to retire. The problem was finding the right suitor. The Carnegie steel empire was very valuable, and there weren’t many people who were wealthy enough to buy it from him.

Fortunately, he found the right person, John Pierpont Morgan. Carnegie was aware of the business sense J.P. Morgan possessed and was excited about making a deal with him. The deal was brokered by Charles Schwab, who had replaced Henry Frick in the position of president of Carnegie Steel.

The sale agreement was finalized in 1901, and Morgan bought Carnegie Steel for $480 million, which, if adjusted to today’s inflation rate, amounts to $17 billion. This was the largest business transaction in American history.

Once the deal was completed, Morgan combined Carnegie’s steel company with several other steel companies to create US Steel, the world’s first ever billion-dollar corporation.

Morgan famously stated in an interview that he was even willing to pay $100 million more for the business.

The final act of redemption

We saw the success of Andrew Carnegie throughout his life. Starting from a humble background, he went all the way to the top. It is completely true that he had to employ some crooked tactics to earn success.

But he seems to have compensated to some extent through the philanthropic work he initiated during his lifetime. He always wanted to be remembered for the good he did, not the money he earned. He started giving out money faster than anyone else.

Carnegie believed that education was very important, and hence he started building libraries. The money he had earned after selling his company was used to make around 2,500 libraries all over the world. He also set up and funded museums, schools, and universities. By the time of Carnegie’s death, he had already donated $350 million. Which was a very big sum those days.

Carnegie Mellon University, formerly known as Carnegie Technical School in Pittsburgh, was founded by Carnegie in 1900. There are also some famous landmarks named after him, for example, Carnegie Hall in New York, USA. This hall was set up by Carnegie in 1891.

He then created the Carnegie Corporation to give away the remainder of his wealth after he was gone and ensure that it went to worthy causes. His final years were devoted to promoting world peace. He even tried to bribe the Germans during World War I to stop the war! He tried to bring all the world leaders together to work harmoniously and stop wars of any kind.

Carnegie saw philanthropy as his way to put things right. Others believe his philanthropy was more about self-preservation. He wanted to ensure that his name would live on and be remembered fondly through foundations, charities, and buildings he set up.

Whatever the reason might be, it is undeniable that he left a lasting mark on the steel industry and helped build America as a dominant power in the 19th and 20th centuries. His innovations in steel manufacturing helped America become a world leader in steel.

In his final years, he even tried to patch up with Henry Frick, his former business partner, but in vain. Frick had already told Carnegie that he would meet him in hell. There is an interesting book you might like to read, Meet You in Hell: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and the Bitter Partnership That Changed America, to get more details of this relationship.

Andrew Carnegie breathed his last breath on 11 August 1919, in Lenox in Massachusetts.