People in history – Robert Bosch

By Kiron Kasbekar | 10 Apr 2024

As a young man, Robert Bosch did not strike people as an ambitious person who might one day become a famous inventor or a big businessman. But he had a craving for knowledge, and a curiosity that later led him on to great accomplishments.

Born on 23rd September 1861 in a small town called Albeck near Ulm in southern Germany, Bosch was the eleventh of twelve children born to a farmer, brewer, and prosperous innkeeper named Servatius Bosch and his wife Maria Margaretha.

Bosch later said he did not much care for that period of his life, nor did he treasure his experience with his teachers or his school. Lacking both the ambition and patience to excel in class, he did well but never excelled. Then, instead of taking up further academic training, he followed his father’s advice and took up apprenticeship to become a precision mechanic.

From 1876 to 1879 Bosch worked in Ulm as an apprentice with precision mechanical and optical instrument maker Wilhelm Maier. Neither Maier nor Bosch took much interest in the work the latter did.

After that he worked as an experienced trainee in various companies until this experience was interrupted by a year of military service. After that a short stint as a student at the Stuttgart Polytechnic gave him familiarity with electrical work.

Not content with studying, and wishing to see the world and gain hands-on experience in industry, Bosch decided to go to America. On 24th May 1884, at the age of 22, he traveled to Rotterdam to board a Dutch steamer headed for New York City.

Interesting fact: The journey from Rotterdam to New York, which took a fortnight by sea in 1884 (for there were no aircraft then) now takes just around 8.5 hours. So, note how much more difficult it was for entrepreneurs to achieve what they did, compared to entrepreneurs today.

Bosch arrived in America after a fortnight at sea, and then found a job in an Edison factory that made a variety of electrical equipment, such as light fixtures, remote-reading thermometers, arc lamps, and phonographs. After a brief stint there and a period of unemployment, he managed to find a job at the Edison Machine Works.

In the meanwhile, after some postal correspondence, Bosch and Anna Kayser, who he had known for long, had decided to get engaged. So, after spending a year in America, Bosch decided to return to Germany.

On the way back home Bosch took a halt in England, where he worked for half a year with Siemens Brothers in Woolwich, near London. Siemens Brothers was a British firm created by William Siemens, whose brother Werner headed the Siemens group in Germany, which is the company we know as Siemens today.

Back in Germany towards the end of 1885, Bosch got officially engaged to Anna Kayser. And then they got married.

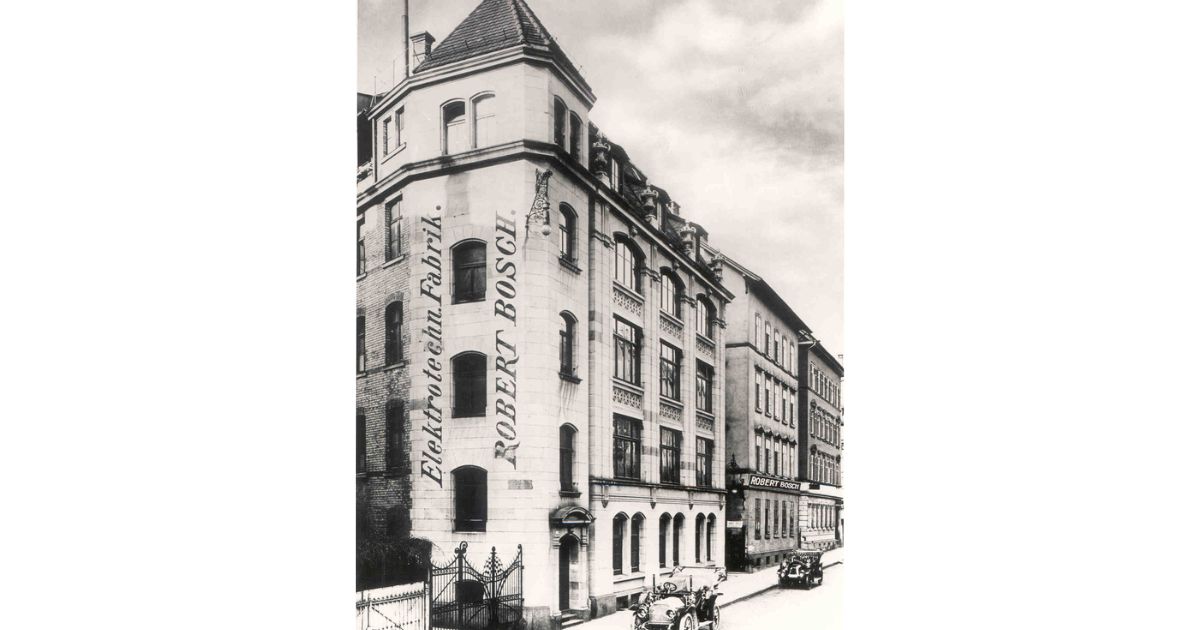

The next year, on 15th November 1886, Bosch opened his own business in Stuttgart, which he called ‘Workshop for Precision Mechanics and Electrical Engineering’.

The workshop which this 25-year-old engineer founded became the launching pad for a company that, 136 years later, in 2023, became a huge global conglomerate with sales of nearly US$99 billion. The huge business group that has been named after him is Robert Bosch GmbH (Bosch), a subsidiary of Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH (Robert Bosch Foundation Ltd).

Everything seemed to be going smoothly. The business was doing better and better, and Bosch had to spend a considerable amount of time running it. Still, he found time for weekend trips and vacations in the countryside with his family. With growing wealth, he had a villa constructed in Stuttgart’s Heidehofstrasse in 1910-11.

The initial spark

In 1887 Bosch introduced the first magneto ignition system for stationary engines, i.e., engines with fixed frameworks, which were used to drive fixed equipment such as pumps, generators, mills and factory machinery.

Such engines were widely used in the past when mills and factories had to generate their own electricity, and power was transmitted by mechanical means, such as belts and gear trains. Their use declined with widespread electrification, which allowed industries to draw power from electrical grids for distributing to various individual electric motors inside the work area.

Robert Bosch got his big break in 1887 when automobile industry pioneer Gottlieb Daimler needed a device to ignite the fuel in his engines, and asked if Bosch could make it. Bosch, fresh off working with Thomas Edison, took on the challenge. He had built a magneto, a spark generator, by modifying an existing design. This seemingly simple act ignited a revolution.

Bosch’s device wasn’t perfect. It was designed for stationary engines, not the fast-paced world of automobiles. Enter Frederick Simms, a visionary who saw the potential for Bosch’s technology in cars. With his help Bosch’s engineers supercharged the magneto, making it faster and more powerful. This innovation received a patent in 1893, a crucial step in Bosch’s journey.

In 1897 Bosch laid the groundwork for future automotive innovations with the introduction of the first commercially viable low-voltage magneto ignition system for internal combustion engines. In 1899 Bosch introduced spark plugs.

The impact was immediate. By 1900, Bosch’s magnetos weren’t just powering cars, they were helping Zeppelins conquer the skies.

From workshop to multinational

By the time the 19th century drew to a close, Robert Bosch realized the limitations of relying solely on the German market to expand the sales of its magneto ignition devices. The automobile industry was still very small, but Bosch had realized the big potential that lay ahead for this industry. So he decided that he must go global.

He opened offices and factories in several other countries, with a staggering 88% of sales coming from outside his home country by 1913. His company had transformed itself from a small workshop to a multinational.

The company established its first international subsidiary in London in 1901. And then it opened its first manufacturing facility in the United States in 1906 to take advantage of the growing demand for automotive components in North America.

In the meanwhile, in 1902, the company had diversified into industrial and consumer goods, introducing its first power tools and household appliances. In 1910 Bosch introduced an electric refrigerator, marking its entry into the home appliance market.

The business had grown; but Bosch wasn’t the kind of person who rested on his laurels. He saw potential for technological advances beyond ignition systems, and began to diversify his company’s portfolio. He ventured into areas like lighting and fuel injection systems.

These efforts ensured that Bosch remained at the cutting edge of the then rapidly evolving automotive industry.

By the close of the 19th century, Bosch foresaw that the market for magneto ignition devices was far bigger than the German market. The automobile was the vehicle of the future, and the future was bound to be big. As a product that fitted so perfectly with the automobile engine, the ignition devices had the potential to break corporate and national barriers to capture the automotive market across the world.

War, boom, and depression

Then the Western world went to war.

On 28th July 1914, the First World War broke out, and businesses were disrupted because international trade could not be conducted routinely as it had been before the war. From 1914 to 1918 Bosch had to go through one of the most tumultuous periods in European history, as did nearly every other major company in the world.

Bosch himself was opposed to profiting from armaments, but the company did benefit from wartime contracts for magnetos. And, despite the challenges of that war, the company continued to innovate, developing new products such as headlights, horns, and windshield wipers for automobiles.

He steered the company through the challenges of World War I and the subsequent economic depression. After the war ended in 1918, the Bosch firm redoubled its research activity.

Bosch had played the waiting game, all the while planning for the future; and by the time the war ended, he was ready to implement his plans. So the company was up and running as soon as the war came to an end.

Robust strategy

So Bosch made a pivotal decision – to venture into key international markets. That was, of course, easier said than done. He needed a good strategy and a great deal of preparation. Cultivating personal connections was vital for gaining access to new markets.

The company participated actively in the Paris motor show, which became fertile ground for networking with industry experts and building important business relationships across borders. Bosch used the show to forge connections with individuals who had intimate knowledge of local markets and extensive experience in selling in those markets.

These connections helped expertly manage the sale of Bosch products, in placed as distant China, from 1909, and Japan, from 1911. However, during that period, Bosch did not go whole hog into establishing subsidiaries and production facilities. Beyond Germany the company ran major manufacturing sites only in France and the U.S.

Bosch’s success hinged on a robust and dynamic sales and distribution network. Robert Bosch, who recognized the importance of strong partnerships with user companies, established close ties with automotive manufacturers, industrial firms, and retailers worldwide. The company used collaborative efforts and strategic alliances to drive up sales by reaching untapped customer segments and entering new markets.

The company prioritized product quality, reliability, and after-sales service, earning the trust and loyalty of customers worldwide. Its unparalleled commitment to customer satisfaction helped expand sales quickly. Bosch’s brand reputation grew and contributed to the company’s long-term success.

Drilling into the future

When the Great Depression hit the world, industries suffered a steep decline. The Bosch automotive products had already suffered a decline in sales before that. The German automotive industry, which was already suffering from a decline in sales around 1925, causing substantial losses at Bosch, was further hammered by the depression that followed the 25th October 1929 stock market crash that threw the entire world off balance.

So Robert Bosch, who was always keenly aware of the need to diversify his business (and had done so with the launch of home appliances) found the answer in drilling equipment, where he realized there was scope for innovation.

The company introduced its first electric hammer drill in 1932. This drill revolutionized construction projects by providing a more efficient way to drill into tough materials like stone, masonry and concrete.

The original Bosch hammer drill used a pneumatic mechanism to create a hammering action while drilling, enabling workers to break through hard surfaces with greater ease and speed compared to traditional drills.

In the meanwhile, all hadn’t gone well in the family. Two of Bosch’s three children died. And his marriage with Anna broke up in 1927. Bosch then married 39-year-old Margarete Wörz, with whom he had two more children.

After the First World War ended, the company continued to grow, getting a boost from the economic boom of the 1920s. In 1926 the company developed diesel fuel injection systems, which were a breakthrough technology that improved engine efficiency and performance.

But Bosch did not want to remain confined to the automobile industry. He recognized the growing importance of household appliances and decided to venture into that business too.

In 1929 Bosch established the Bosch Research Center to expand its research and development activities and drive innovation across various industries.

In 1932 Bosch introduced the first anti-lock braking systems (ABS) for automobiles, demonstrating the company’s commitment to automotive safety.

The home market

With increasing industrialization, and growing prosperity, a segment of the population was interested in and able to purchase various consumer durable products that were beginning to come to the market. So Bosch began making power tools, washing machines, and refrigerators. Soon it itself as a household name in innovative consumer durables.

Bosch made its debut in the refrigerator market in 1929 with a unique, round model. This compact, cylindrical-shaped design targeted smaller kitchens and claimed to be more energy efficient than other fridges in the market at the time.

The innovative design did stand out in the marketplace, especially after heavy advertising by Bosch about the refrigerator’s benefits, such as convenience, food preservation. But refrigerators remained a luxury for most European households, and Bosch’s cylindrical model could not break through that perception.

Also, consumer opinions on the cylindrical shape were mixed. What else did Bosch really expect? The company responded in 1935 by introducing rectangular-shaped refrigerators with larger capacities. It kept improving its refrigerators with features like interior lighting and adjustable shelves.

By the 1950s, with more affordable models, the Bosch refrigerator became a staple in many kitchens.

Dealing with difficulties

The 1930s were a difficult period for business, which had just emerged from the Great Depression that had begun in 1929. But, because of its strong position in its various product markets, Bosch managed to maintain steady growth, and to expand its product portfolio to include telecommunications equipment and industrial machinery.

Robert Bosch steered the company through the challenges of World War I and through the boom of the 1920s, the depression of 1929 that followed and hobbled business until the Second World War broke out and disrupted business further.

Given its strong market position, the company continued to survive and do well. And after the Second World War ended consolidated its position, and expanded in all its markets.

Sadly, while the war was still raging across Europe, Robert Bosch breathed his last on 12th March 1942, at the age of 80. The company marched on, led by others he had recruited, trained and groomed for taking on responsibility for the various businesses.

The businesses continued to grow, and in 2022 the Bosch group chalked up revenues of €91.6 billion, i.e., U$99.38 billion. That was higher than the sales revenues of most of the automobile companies which are its customers!

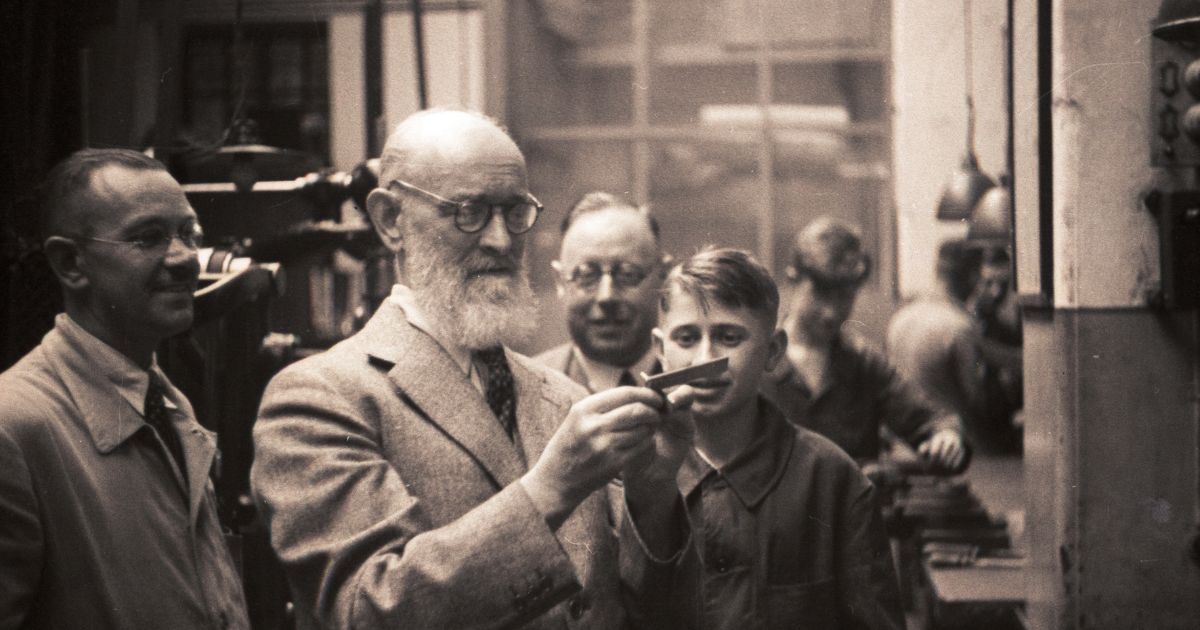

At the heart of Bosch’s management philosophy was a deep-seated belief in the importance of people. Bosch fostered a corporate culture characterized by teamwork, integrity, and innovation. He believed in empowering employees, fostering a collaborative work environment, and encouraging creativity and initiative at all levels of the organization.

Bosch’s leadership style was marked by a hands-on approach and a keen focus on operational excellence. He emphasized efficiency, productivity, and continuous improvement, driving his workforce to achieve peak performance. Bosch’s management principles laid the foundation for a resilient and adaptive organization capable of navigating the challenges of a rapidly evolving business landscape.